Sacred Disorder | Cliff Bostock's blog – 'Finally, I came to regard as sacred the disorder of my mind' (Rimbaud)

Why do we act so dumb on the Internet?

I posted a video a few days ago on Creative Loafing’s Omnivore blog featuring a couple of Domino’s Pizza employees who exhibit some pretty disgusting behavior in the kitchen. One filmed the other while he inserted a sandwich’s cheese up his nose and farted on the meat.

Having worked in concession stands at Six Flags Over Georgia when I was a teenager, the most shocking thing about the video to me isn’t the content but the fact that the two incriminated themselves on YouTube. I can well remember wanting to poison customers myself and while I don’t remember doing anything quite as disgusting as these two, I do remember cheerfully revising the absurdly complicated instructions people sometimes gave for the preparation of their burgers and hot dogs — a mound of dehydrated onions when they demanded none too arrogantly, for example.)

As it happens, I was browsing the Net about the Domino’s incident and found this blog entry by Hal Niedzviecki, author of the forthcoming book, The Peep Diaries: How We’re Learning to Love Watching Ourselves and Our Neighbors. In his post, Niedzviecki confesses his own youthful experience in the fast food industry and, like me, is mainly shocked that the two kids documented their behavior. He relates the behavior to his new book, which is about the way the culture has become obsessed with a kind of shared voyeurism — “peeping” at one another, through YouTube videos, memoirs, blogs, social networking sites, reality TV shows, ad inifinitum. Obviously the impulse to be seen overrides all else.

Not what Ronald McDonald usually does

Not what Ronald McDonald usually does

As further evidence, he cites the incredible story recounted in the video above. In 2004, a young employee of a McDonald’s in Kentucky was stripped, humiliated and sexually assaulted by two others under telephone direction of someone pretending to be a policeman. The entire drama was caught on a security camera. Niedzviecki, more respectful than me, doesn’t link to the video but notes that ABC’s broadcast of it is exemplary of the “peep culture’s” shattering of all traditional boundaries of privacy.

He makes the point in his own YouTube video that, having watched the media incessantly peep into the lives of celebrities, the rest of us somewhere along the way decided that if we can make ourselves “peepable,” perhaps we’ll become rich and famous, too. And, really, after marveling at the stupidity of the people involved in the McDonald’s incident, you can’t do anything but marvel more that they consented to being interviewed by ABC and, apparently, authorized broadcast of their sex scene. It seems that, like the Domino’s pair, it’s more important to be peeped than to appear sane. I know this has been happening at least since Jerry Springer’s show, but now the entire culture seems to be auditioning for a freak show.

The degree to which this has overtaken us has become especially apparent to me since joining the world of Twitter and FaceBook about a month ago. FaceBook has been fun because it has allowed me to reconnect with long lost friends and have more personal interaction with some readers of my work. It’s also been cool to meet people who share some of my more arcane interests.

But both FaceBook and Twitter also invite us to broadcast stray thoughts, one-liners, bits of personal news and links to stuff we like on the Internet. In some ways, it’s very democratizing. I’m following a few major writers and critics and it’s cool to watch their brains firing randomly.

But I’ve also noticed a very strange phenomenon — the way some people manage to create a huge amount of self-buzz that doesn’t have much to do with anything other than…the self-buzz. I’m not going to name names but a typical example goes like this. I log onto a website and read a bio that seems to include some very impressive accomplishments.

Then I follow links and find that this person has created dozens of profiles on social and professional networking sites, plus YouTube and such. The more I follow the links, the more impressed I am and the more miserable I feel about my own little life. Then I notice that their YouTube videos might have only a couple hundred views. Their profiles on Facebook may have a comparable number of friends. I look at the documentation of, say, all the articles they’ve written and notice that they have literally kept track of every paragraph they’ve ever published, so that there’s no effective differentiation between a magazine cover story and a blurb somewhere.

Meanwhile, the person is tweeting two, three or more times an hour, even while driving. He is “friending” everyone he can on Facebook, no matter how tangential, ephemeral, abstract or — let’s face it — fictional the relationship. He’s got 2,099 friends. My God, he must be a star!

The more I look, the more I realize the person’s apparent significance is mainly an effect of self-promotion, manufactured appearance, than demonstrable talent and experience. Here and there, now and then, they float to the surface in a genuinely public way but the occasional 15 minutes of fame is stitched together in such a way that it can appear like an endless, ongoing heroic tale.

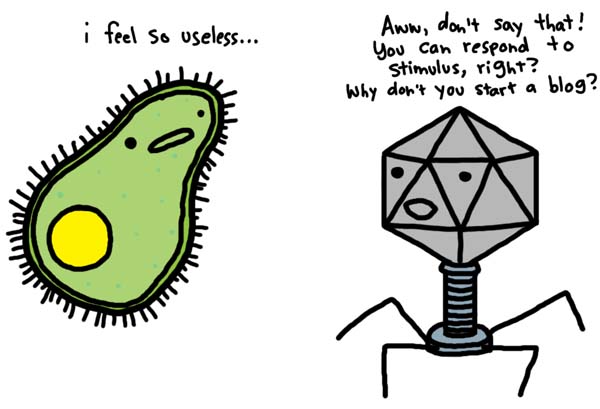

Is it just stimulus and response?

I was discussing the phenomenon with a client, a scientist, recently and he urged me not to discount the simple effect of stimulus and response. Facebook and Twitter “poke” us and we, as inherently social creatures, poke back automatically, he suggested. In that, it’s not much different from usual human interaction. The difference is that in cyberspace we have relatively instant access to multiple people at once. (And, of course, we have much more control over the duration and nature of our interaction.) All that poking puts the entire culture in a state of heightened stimulation.

I don’t think any of this is a bad thing. As I’ve recounted in essays over the last few years, I’m fascinated with the use of cyber communication in psychological work. I’ve worked with a handful of individual clients and a group in blogging as part of our interaction. Perhaps it’s a bit like Freud sitting behind the sofa, out of immediate view of the free-associating client, but I’ve repeatedly seen material arise in blogging that doesn’t find its way so readily into real-time conversation.

I don’t think any of this is a bad thing. As I’ve recounted in essays over the last few years, I’m fascinated with the use of cyber communication in psychological work. I’ve worked with a handful of individual clients and a group in blogging as part of our interaction. Perhaps it’s a bit like Freud sitting behind the sofa, out of immediate view of the free-associating client, but I’ve repeatedly seen material arise in blogging that doesn’t find its way so readily into real-time conversation.

So I can’t discount the possibility of the unconscious exhibiting itself more actively in this medium. Maybe the medium itself inflates the elemental need to see and be seen into a kind of virtual voyeurism and exhibitionism. As has often been observed, the psyche in its depths — in dreaming, for example — has very little sense of political correctness or general propriety. There’s also a sense of the self as an other in dreaming. We dream “about” ourselves. Likewise, there’s a kind of otherness to the cyber-self even in literal video representation, I think. The medium grants us the freedom to show our “other” side.

Of course, the presence of the camera and the eventual screening on TV and in cyberspace were unknown in the strange case of the McDonald’s sexual assault, even though the disembodied voice of the faux cop similarly may have exploited the blank projective space created by most forms of communication technology. But by the time the protagonists of the drama authorized ABC to tell their story, replete with video, they had surely become others to themselves. The woman who initially strip-searches the young woman seems quite earnestly to describe behavior completely opposite to what’s exhibited in the video. I would love to hear interviews with the two Domino’s kids, too.

Whatever the mechanism, it seems quite clear to me that our cyber-selves can attain autonomy enough to behave quite differently from our understanding of our real-time selves. The moral, which I’ve yet to master fully myself, is to ask ourselves who is in control when we are about to hit the Twitter or video upload button.

(Blogging graphic above from Nataliedee)

True dumb asses at work

I find this video clip from last Sunday’s “This Week With George Stephanopoulos” astonishing. Here we have a group of Washington pundits seated about a table, agreeing that the Bush administration monsters who devised torture routines enhanced interrogations should not be prosecuted.

Particularly reprehensible is Peggy Noonan, who worries that “Somethings in life need to be mysterious.” We should simply look the other way and “keep walking.” Indeed, the recently released memos that read like instructions to the torturers of the Spanish Inquisition should not have seen the light of day. What possible good could come of admitting error, much less literal prosecution of people who only meant well by subjecting detainees deprived habeas corpus to simulated drowning nearly 200 times within a month?

What this video exemplifies is Hannah Arendt’s famous description of “the banality of evil” by which the most heinous, inhumane acts are normalized. That these people are supposed to be “watchdogs” of the Fourth Estate is more evidence of the complete corruption of media. They are literal complicitors in the normalization of torture and the Orwellian use of language to render it something less than the horror it is.

The “banality” extends of course to the depth of their own intellects. There’s no need for these “journalists” to consider Constitutional law or the Geneva Accords and other international treaties. Moral and ethical inquiry are completely beside the point.

They sound like high school sophomores trying to excuse a practical joke that went bad.